Ingleside Plantation – North Charleston – Charleston County

Basic Information

- Location – Bluehouse Swamp, North Charleston, St. James Goose Creek Parish, Charleston County

Northside Drive

- Origin of name – We do not yet know why this plantation was renamed Ingleside. See below for the origin of the name Hayes.

- Other names – This plantation was originally called Hayes. It was renamed in the 1870s. "Hayes" derives from the name of the ancestral home of the Parker family in England, Hay-on-Rye (1).

- Current status – Most of the now 2,000-acre property is being commercially developed; the development is slated to be the largest and most dense in South Carolina, encompassing commercial space as well as up to 100 homes per acre. The brick ruins of the house will be preserved (6).

Timeline

- Circa 1694 – John Parker I received a warrant but died before he took possession of the land. The grant was then issued to his widow, Sarah Parker. Sarah married John Barker (4, p. 40) (5, p. 18) (7, p. 252).

- 1716 – Sarah Barker gave 600 acres to her son, John Parker II. John Parker II established Hayes Plantation. Hayes Plantation would be passed down to the eldest Parker male for over 160 years (1) (4, p. 40) (5, p. 18) (7, p. 252).

- Early 1700s – House built by John Parker II (1).

- 1735 – John Parker II lived at Hayes Plantation until his death. The property then passed to his son John Parker III (4, p. 185) (7, p. 252).

- 1793 – John Parker III divided Hayes Plantation into two sections. The eastern section, which was 932 acres and included the house, retained the Hayes Plantation name and was given to son John Parker IV. John Parker III gave the western section to son Thomas Parker. Thomas called his plantation Woodlands (1) (4, p. 185) (5, p. 19) (7, p. 252).

- Circa 1832 – John Parker V inherited the plantation, most likely after the death of his father in 1832 (1) (7, p. 252).

- 1849 – Dr. Francis Simons Parker continued the legacy of Parker proprietorship, having purchased the plantation from his father, John Parker V. Dr. Parker also owned Mansfield Plantation and Greenwich Plantation (1) (7, p. 252).

- 1865 – Dr. Francis Parker died and left Hayes to his children (1) (7, p. 252).

- 1871 – The Parker children sold the plantation to Professor Francis Simmons Holmes. Holmes renamed the plantation Ingleside. Holmes experimented with growning rice at the plantation until the late 1870s (1) (4, pp. 185-187) (5, p. 19) (8, p. 244).

- 1886 – The house was damaged by an earthquake (5, p. 19).

- 1914 – The house was lost to fire (1). Its brick ruins remain today.

Land

- Number of acres – 600 in 1716; 1,166 in early 1700s; 932 in 1793; 1,282 in 1802; 702.5 in 1871 (1) (4)

- Primary crop – Rice

Professor Holmes continued to experiment with rice long after slavery ended. Some sources say he was the last ...

- Cemetery – Several members of the Parker family are buried at Ingleside.

- The Middleton Oak

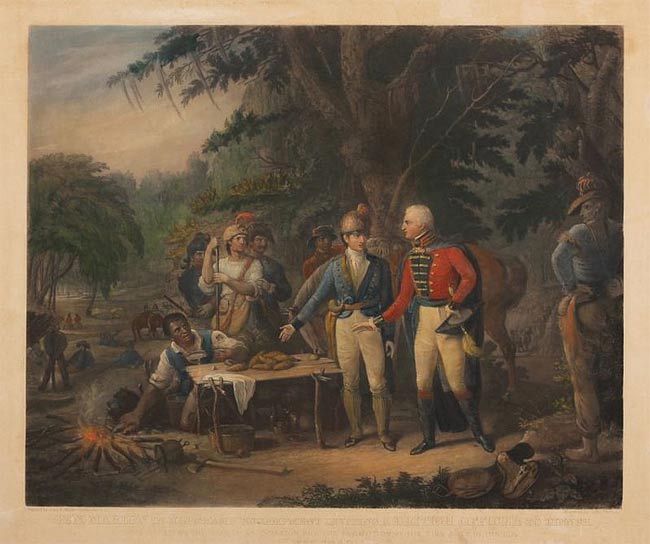

Hayes Plantation was home to the famous Marion Oak, a live oak tree that is said to have served as the site of a supper hosted by General Francis Marion for one of his rival British officers.

-

The tree no longer exists but survived until at least 1908 or 1909. Contemporary descriptions place the oak within or near a double row of cypress trees located on a slope behind the Ingleside home.

Below is the story of the Marion Oak as recorded in Good Housekeeping in 1906.

In many a home, a generation ago, there hung in a place of honor an engraving representing General Marion's entertainment of General Cornwallis. The British forces then in Georgia and South Carolina has been very seriously hampered by a brigade of guerilla warriors, under the command of Marion, better known to Revolutionary History as the Swamp Fox. He had successfully escaped every attempt at capture. Cornwallis, the story tells us, wished to argue the English cause with him, in the hope of winning him to take a compensation from the crown. So the British general had sought this interview in Marion's camp. The picture shows a rude table beneath a spreading oak tree. Ragged soldiers stand behind General Marion, who is pointing to a few sweet potatoes heaped on the table, evidently inviting his guests to dine; while Cornwallis and his companions, by contrast very richly dressed, are pointing in surprise to this evidence of poverty. Beneath the picture were written the words, "We can never conquer men who are willing to undergo such hardships." This sentiment has raised a question in many a boy's mind. Why should the Briton have scorned good roasted sweet potatoes? Even in the engraving they looked appetizing, spread, as they were, beneath a tree which the artist had constructed on generous if unfamiliar lines. Perhaps such questions have lingered on the far edge of the reader's memory, not consciously thought of these past forty years. They had so lingered in the minds of a few visitors in the southland, which force sufficient to send the hunting for Marion's oak.

Turning from Marion's oak, the visitor finds the land on which it stands of hardly less interest. It was the planation, and upon it may still be found the homestead, of John Parker. The man and the place illustrate the sort of southern men who made this valley their home, and the kind of setting which a prosperous planter of pre-Revolutionary days chose for his life of work and pleasure.

Parker was born in Charleston in 1749. Educated abroad, and graduated at the Middle Temple in London, he returned to Charleston in 1775, married a sister of the famous Arthur Middleton, and settled upon this land, which was then – as it continued to be down to the time of the war – a rice plantation. From 1786 to 1788 he represented his section in the Continental congress. He was a man of prominence and influence in local affairs. These facts lend interest to his estate, which, tradition claims, remains practically as he laid it out.

One approaches the homestead from the famous oak through a beautiful shaded avenue. On either side are the rice swamps, or flooded fields, long since left idle, showing moss covered limbs reflected in the still water. Her on a small island stood a summerhouse prettily shaded; but the bridge that once connected it with the driveway has almost disappeared. Farther on one comes upon part of a magnificent avenue of cypress trees, standing ninety odd feet high, straight and stately, like guardians over the past. If indications may be trusted, this avenue formerly half circled that part of the estate which bordered on the water, but now not more than twenty trees are left standing. Yet these trees in their stately beauty, their branches draped in the soft moss that looks like the veils of the gray nuns, would alone well repay a visit to Ingleside.

Passing from this cypress avenue, the visitor comes upon the Parker homestead. It is a square, substantial, brick building, two stories and a half in hight [sic]. It appears to have had a porch across the front, somewhat narrower than the modern one now standing. The original roof had a row of dormer windows along the front and sides, and was higher than the present roof and different in shape. This was demolished by the Charleston earthquake. Long cracks on the sides of the house and on the chimneys mark this same catastrophe.

The interior of the homestead is of the simplest arrangement. Below stairs there are four rooms of about equal size. The front door leads directly into the largest of these, which was at once hall and living room. Three doors open from this largest room. One on the right leads into a large bedroom; one at the left and back leads into a smaller living room, and one directly opposite the front door gives access to a narrow hallway. On the side this opens into the dining room, and at the rear, by a door that duplicates the front entrance, on a back porch.

The hall contains the stairway leading to the floor above. In itself this staircase is very beautiful. Turning at the foot, turning again beneath a large window half way up, and again turning to reach the upper landing, the bannisters gracefully fashioned in the spindle design, its steps broad and easy to tread, it would be an ornament to any mansion. But here it is crowded into a very narrow space and has not near room enough to reveal its beauty. Like the wainscoting on the walls of the rooms above and below stairs, this wood work shows the earnest attempt of the builders, with inadequate means and tools, to reproduce the dignity of the English homes to which they were attached. These attempts led the way to the later and more perfect colonial design which fortunately are now so familiar to us in reproduction.

This example of "early colonial" stirs our curiosity. We wonder for what purpose Madam Parker used the low basement kitchens, with their wide, deep fireplaces. How did she decorate those high, bare windows, and what pictures did she hang against the wainscoting? In the times of those marriage parties and merrymakings, which [of] these old rooms must have witnessed, where di Madam Parker stow away her guests, who doubtless made their pilgrimages from Charleston, as well as from the neighboring estates?

One incident shows us how unsettled were the times. With British soliders in Charleston, the countryside was none too safe. Madam Parker was sitting in a window seat in the living room when a drunken soldier, passing by, fired his pistol at her. The bullet just missed above the fireplace, where it may still be see. John Parker was at hand, and promptly shot and killed the soldier. He was wise enough immediate to sent an account of the affair to the British commander, whose brief reply is much to the point: "Sir," he wrote, "I have received your communication. I am glad you fired."

In front of the homestead stretches a beautiful open field, marked by a quarter-mile race course that passes the door. Parker not only knew fine horses, it would seem, but knew also how to enjoy them. What lover of horses could fancy anything more delightful than a good speedway in front of his house! To the left of the race course, and near to it, is the family burying lot, typical of the custom of burying the dead near the home instead of in public places. Here lie the remains of John Parker and the members of his immediate family.

Within recent years the estate passed out of the possession of the Parker family, who still are distinguished citizens of the locality, and is now no longer occupied. The reasons are not far to seek. The knowledge and consequent dread of malaria at certain seasons deters people from living here. Rice growing, which made the wealth of this region, since the war is of no advantage. It might easily be profitable now, as it was formerly, if laborers could be found to work the plantations. In this section, at least, the plantation days, which made this old homestead the center of a busy, happy life, have famished never to return.

Leaving Charleston, that fair city of romance and tragedy, where many a monument bespeaks the bravery of a people that seldom has been equaled, a city of such beautiful homes and public buildings that the visitor is tempted to stay on indefinitely, one has to travel only half a day to Ingleside to find the very tree beneath which Marion met Cornwallis. The century and a third that have passed since it witnessed that meeting have treated it roughly. Lightning has severed its trunk, splitting it to the ground; but from the limbs so broken new branches have long since put forth a stolid growth. Even in its decrepitude the tree still spans nearly a hundred feet. And one may stand to-day beneath its shelter, where Cornwallis doubtless felt the conviction, whether or not he spoke the words attributed to him, that he was fighting men who were willing to undergo any hardship for their cause. What the charter elm is in Connecticut tradition, the sturdy tee is to the history of South Carolina. It is to be hoped that one of our patriotic orders, which are doing such good work preserving national landmarks, may some day be able to shield this historic tree for any future chance of ruin.

Slaves

- Number of slaves – 34 under John Parker, II (4, p. 185)

Buildings

- The plantation's brick manse was lost to fire in 1914 (1). The excerpt below appears in Historic Houses of South Carolina and provides a description of the house written by Anne Simmons Deas, a local diarist.

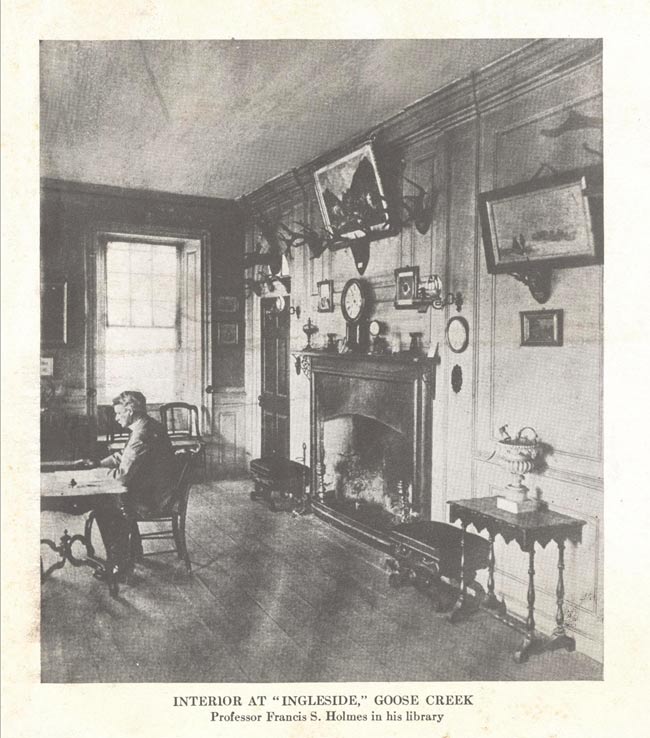

Ingleside Hall on Goose Creek, not far from Dorchester, was formerly the residence of Hon. John Parker, a member of the old Congress (1774-1789) who was born in 1749, married Miss Susannah Middleton and died in 1822. It was bought afterwards by Professor Francis S. Holmes, a descendant of Landgrave Smith, and developer of the phosphate deposits of Carolina, and an existing picture presents the interior of the house and shows Prof. Holmes in his study.

Francis Simmons Holmes (1815-) was the son of John Holmes and his wife, Anna Glover. While a youth of about fourteen years of age he visited England with a maternal uncle by marriage, a Mr. Lee, of England. Returning to America he engaged for a number of years in mercantile pursuits, in which, however, he was not successful, so removed to St. Andrew's Parish and devoted his attention to agriculture. Experience taught him that a knowledge of the science of geology was essential to an intelligent planter. In the pursuit of this study he obtained the friendship of the leading geologist of the country, Professor Agassiz, a letter from whom is found in the scrap book of F. S. Holmes, a great-nephew of Prof. Holmes. A similar friendship was also formed with Count Pourtales, an engineer, who came to this country about the same time that Agassiz and Dr. Holmes became intimates. He became connected with and was assistant to Prof. Price, U. S. Coast Survey, and visited Prof. Holmes for six weeks with Agassiz at Ingieside.

Prof. Holmes is best known in connection with the discovery of the commercial value of South Carolina phosphate rock for fertilizing purposes, and that he was no ordinary man is manifested by the fact that the boy who left school at the age of fourteen, by his own application, energy and perseverance fitted himself for a professor's chair in Charleston College which he held until the Confederate War, when he was appointed to office in connection with coast defenses and became chief of the Nitre and Mining Bureau in South Carolina and Georgia. Upon his withdrawal from the professorship at the College of Charleston he generously left in the museum his entire collection of fossils, said to be among the largest and most valuable in the country. The commercial prosperity of Charleston in the field of fertihzer industry rests largely upon the scientific achievements of Professor Holmes, whose knowledge was ungrudgingly given to his fellow-citizens, and who received from abroad and at home many marks of appreciation of his genius and position.

Ingleside, a colonial country house, is described by Mrs. Deas as being "situated on the crest of a gentle elevation; a square, hip-roofed brick dwelling having two stories and an attic; and sufficiently high from the ground to admit of rooms beneath." These rooms, however, did not form a basement, as the floor was some steps below the level of the ground and really constituted a crude fort.

The front door opened directly from the porch into a large room, and from this a door gave entrance into the other and smaller front room. The back rooms were separated from each other by a narrow hall, in which the staircase with its heavy balusters were placed. Under the stairway was a flight of steps leading down to the basement.

There were four rooms on a floor, those on the first floor being connected in pairs by the "Thoroughfare closets" so common in old houses. The rooms were wainscoted halfway up, and had deep, low window-seats ; the window sashes were broad and heavy, and the shutters of paneled wood. The back door was unusually thick and heavy, being built, so tradition says, to resist Indian attacks in the early colonial days.

The view from the front windows was over a level field stretching off to the woods. Near the end of the field a clump of trees marked the family cemetery where stands the Parker shaft. Ingleside was for many years the property of the Parker family, its original name being "The Hays."

At the time of the Revolution, when the plantation was owned by Mr. John Parker (whose wife was a Miss Middleton), the British were marauding near Ingleside one day, and while Mrs. Parker was sitting near a window sewing a party of these marauders came up the avenue and fired at her. Fortunately the ball missed Mrs. Parker, but struck the wall, and the hole it made could be seen for many years.

A gentle slope leads from the back of the house to the "lake," where a double row of towering cypresses makes a romantic walk on the very edge of the water. The lake was used as a reservoir for irrigating the rice field. Following the causeway along its banks and crossing a field brings a traveler to a giant live oak known in tradition as "Marion's Oak," but someone has facetiously remarked that if Marion dined under all the oaks under which he was supposed to have given his famous sweet potato dinner he would have had no time for fighting, but would have spent his time as uselessly as popular tradition would have us believe George Washington did, viz., in sitting in the numberless "Washington Pews" and sleeping in the numberless "Washington Beds."

References & Resources

- Information contributed by Frost Parker from:

William Henry Parker, Genealogy of the Parker Family of South Carolina (1933)

- 30-15 Plantation File, held by the South Carolina Historical Society

- Claude Henry Neuffer, editor, Names in South Carolina, Volume I through 30 (Columbia, SC: The State Printing Company)

Order Names in South Carolina, Volumes I-XII, 1954-1965

Order Names in South Carolina, Volumes I-XII, 1954-1965

Order Names in South Carolina, Index XIII-XVIII

Order Names in South Carolina, Index XIII-XVIII

- Michael J. Heitzler, Goose Creek: A Definitive History - Volume One: Planters, Politicians and Patriots

(Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2005)

- National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form - PDF - submitted in 2001

- Information contributed by photographer Gazie Nagle.

- Winfield Scott Downs, editor, Encyclopedia of American Biography: New Series, Volume 9 (New York, NY: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1938), pp. 252-254.

- Michael J. Heitzler, The Goose Creek Bridge: Gateway to Sacred Places

(Bloomington, IN: Author House, 2012)